A conversation between Jacques Leenhardt and Jean-Marc Poinsot

Jean-Marc Poinsot. We created the Archives de la critique d’art (ACA) (Association for the Archives of Art Criticism) together in 1989, but the adventure began a little before that.

Jacques Leenhardt. Indeed, it began with a small notice I spotted in Le Monde, stating that the Getty Institute was hoping to acquire the archives of Charles Estienne. It’s worth recalling that Estienne was a well-known critic in the 1940s and 1950s. This short notice instantly alerted us to the risk that not only these archives – but others, too – were liable to be snapped up, either by the Getty or by one or other of numerous museums and universities in the States that had an interest in this kind of material. At the time, I was President of the French Section of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). For me, this information was like receiving an electric shock, and I said to myself: if we leave it to the American institutions, with their powerful financial resources, to expatriate all the French critics’ archival holdings to the US, we soon shan’t be able to study the history of our own contemporary art in France!

J-M.P. When was that?

J.L. That was in 1985 or 1986. The earliest correspondence between us about archives that I can trace dates back to 1987. You were then a board member of AICA France and currently head of documentation at the CAPC Contemporary Art Centre, in Bordeaux. I told myself that, logically, you were the best qualified of all of us in this field. There was no question of creating an archive at this point, but rather of assembling the relevant documentation. And this was the moment, at which I telephoned you, to suggest we put our heads together to examine the problem. Around this time, we also made an appointment to see Madame Paradis, who represented the Getty in France. Given that we couldn’t by any means count on the Getty’s collaboration, we had envisaged creating our own organisation for preserving the archives of art critics belonging to AICA and sought help from a number of European institutions. Fortunately, it became possible, later on, to collaborate with the Getty Institute.

J-M.P. We also had several meetings to discuss, first databases, then the Internet, which got going around then.

J.L. With one or two exceptions, such as the Bibliothèque Jean Laude, in Saint-Étienne, the museums and large institutions in France did not show much interest in preserving the work of art critics. Pierre Restany, too, used to complain that no one seemed to be interested in helping to preserve his output.

J-M.P. We then began to articulate the project that would eventually develop into the the Archives of Art Criticism, and it happened in the following way: Dominique Bozo, who had just been appointed to the Visual Arts Department (DAP) of the Ministry of Culture[1], decided that he wanted to develop an original project for the Villa Gillet, in Lyon and was casting around for a director capable of proposing a suitable programme for it. When he approached me about this, I presented to him our project for an Archive of Art Criticism. That was when we began to look into the idea seriously, and Dominique Bozo then gave us a green light to go ahead. Françoise Chatel, whose was then the Regional Counsellor for the Visual Arts in Brittany, was in a position to give us a grant to work up a preliminary proposal. That was in 1989. It made it possible for us to put together an initial working group and establish an ad hoc association.

Quelles mémoires pour l’art contemporain ?, Actes du XXX e Congrès de l’AICA, Rennes, 25 août-2 septembre 1996, fonds AICA International [FR ACA AICAI BIB IMP057], collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. Lire en ligne.

J-L. I had, in fact, made preliminary approaches to three critics – Michel Ragon, Pierre Restany and Georges Boudaille – from the moment that we were given the green light. By agreeing to donate their archives to the future institution, these three key figures constituted a kind of guarantee that our project was feasible.

J-M.P. Yes, you must have spoken to Michel Ragon at the time, because he had just donated his archives on abstraction to the Museum of Fine Arts in Nantes, to supplement the donation from Gildas Fardel, but seems to have been disappointed that nothing came of this after the closure of the exhibition Autour de Michel Ragon (2010), which had been organised to mark the event.

J.L. There had, indeed, been a colloquium at the museum in Nantes at the time of the exhibition, and I had taken part in that. This was the occasion on which I had first raised with Ragon the question of the future of his archives.

J-M.P. That’s when things began to mature. Thus, for example, just as we were getting our project together, the Biennale de Paris was going through the process of liquidation. From one day to the next, we had to get hold of a lorry, to prevent all the documents from being chucked into the dustbin.

J.L. It so happened that Georges Boudaille, who had been President of the French Section of AICA, was the Director-General of the Biennale, and this was how we could salvage the material, in 1990.[2]

J-M.P. Going back to 1989 for a moment, when I began to discuss our project with Dominique Bozo, he gave me his consent, on the condition that there would be no overlap with the Centre Pompidou’s documentary holdings. This amounted, more or less, to undertaking not to encroach on the first half of the twentieth century. This made it essential for the Archives to begin with living critics and criticism that still had a currency – i.e. that had appeared after the Second World War, with writers such as Michel Ragon, Pierre Restany, Franck Popper and Alain Jouffroy.

Création des Archives de la critique d’art. Manifestation inaugurale, Université Rennes 2, 16 décembre 1989. De gauche à droite : Jacques Leenhardt, Michel Ragon et Thierry de Duve, photographe : Loïc Lamandé, archives internes ACA, collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. D.R.

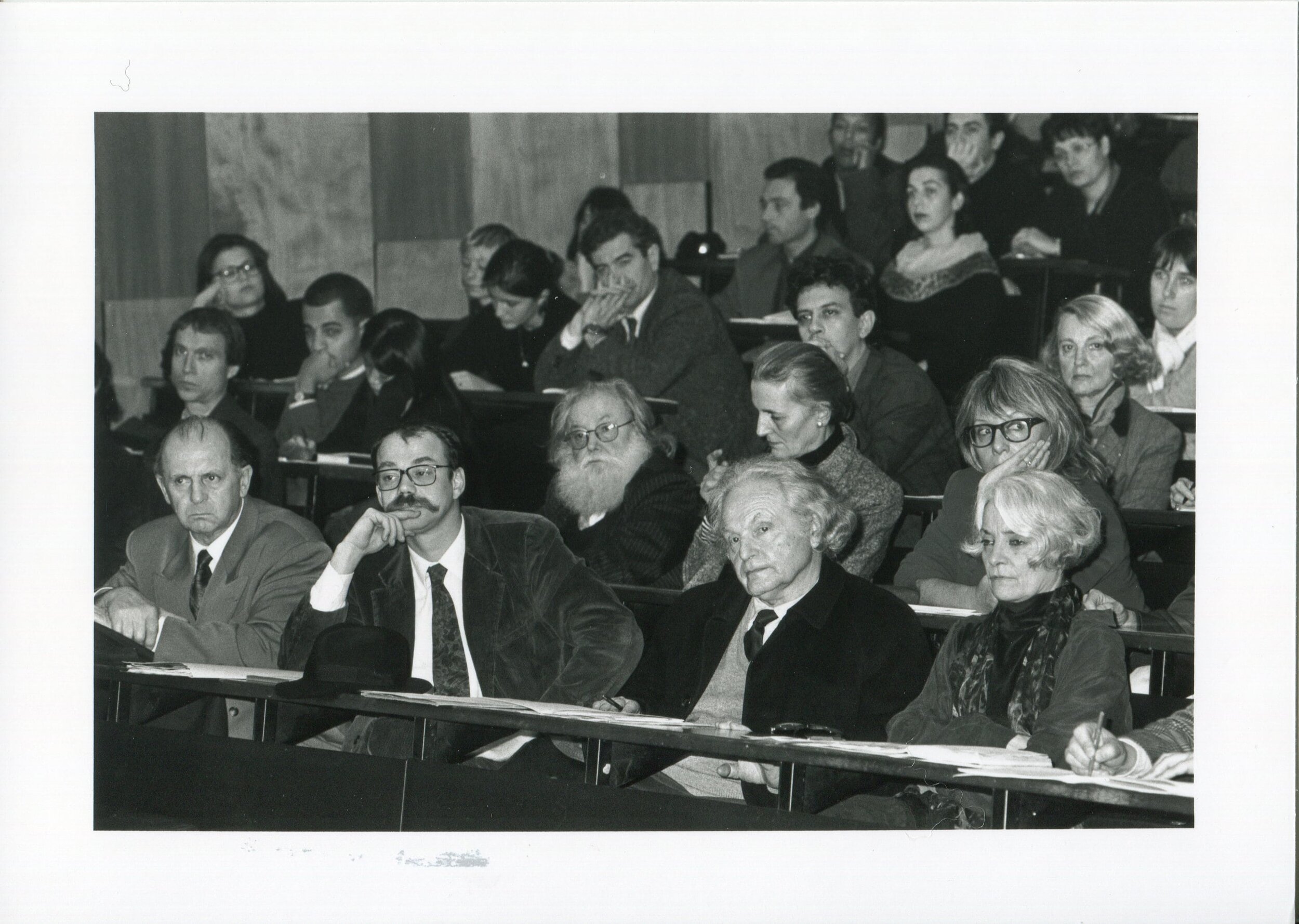

Colloque La Critique d’art en Europe, Université Rennes 2, 20 novembre 1992. De gauche à droite, premier rang : Pierre Le Treut, Harry Bellet, Frank Popper, Marie-Odile Briot: deuxième rang : Pierre Restany et José-Anne Decock-Restany: troisième rang : Ramon Tió Bellido, Anne Dagbert, photographe : Loïc Lamandé, archives internes ACA, collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. D.R.

Soon after this, Restany donated his first tranche of material to the Archives.[3] This was followed by several more batches, although there were a few tricky moments after his death. The portion of the archives which had remained in his flat was at risk of being scattered, but happily we were able to persuade, first his widow, then his heirs, to help us to finish off the work we had already started.

J.L. At all events, what seems to me to have been decisive was the fact that you have succeeded ever since in enlisting the support, both of your own colleagues and of their students at the University of Rennes 2.

J-M.P. Yes, at the time when we were putting together the Archives, André Lespagnol, an historian colleague of mine, whom I knew well, became President of the University of Rennes 2. He had then proposed naming me Vice-President of his Academic Council, but I told him I would prefer to prioritise the Archives de la critique d’art. He supported me in my decision and proposed quickly putting together an agreement which, very importantly, included access to IT facilities and university personnel with a specialist background in information science and technology (URFIST). Once the project had taken shape in our minds, I made formal approaches to the City of Rennes and the Region. In my capacity as Artistic Counsellor in the Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs (DRAC), from 1979 to 1981, I had had dealings with Pierre Le Treut, the Vice-President for Culture for the Region of Brittany, and I came across him again on the advisory committees of the new Regional Fund for Contemporary Art (FRAC), that I had pioneered in 1980. Le Treut also happened to be the Mayor of Châteaugiron, ans he had managed to set up the FRAC. He had sought my help in identifying a suitable candidate for the post of director, and I suggested the name of Catherine Elkar for this position. Elkar, who had enrolled as an intern at the Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs (DRAC), at the time when I was setting up the FRAC, had become a full-time member of the FRAC team, when this was first established, and Pierre Le Treut decided to offer her the position of interim director. I encouraged her to accept this post, and that is how she took over the role of director. As she knew very well that I was looking for premises, she then offered us the use of the old school building where the FRAC was going to be installed, but which had not yet been completely renovated, and so we moved in there. In the beginning, the Archives of Art Criticism were installed on the ground floor, which they shared with the FRAC team. Two years later, they moved up to the first floor, which had been renovated in the meantime and adapted to our needs, thanks to the support of the Region, the Department and the DRAC. We were very comfortably installed then. In the meantime, the small group making up the Association’s Scientific Advisory Committee had organised a certain number of public meetings at the University of Rennes 2 and at other locations, such as the Museum of Fine Arts and the National Theatre for Brittany (TNB). One of the first of these was held with the participation of Michel Ragon, Marc le Bot and ourselves. It was followed in 1990 by organising the first true colloquium, on ‘The Place of Taste in the Philosophical Production of Concepts and their Critical Destiny’ (La place du goût dans la production philosophique des concepts et leur destin), with the aid of a team put together by the AICA office in Paris, including Élisabeth Lebovici, Didier Semin, Ramón Tió Bellido and others. [4]

J.L. This, then, was also the first publication produced by the Archives!

J-M.P. Yes. After this inaugural event we invited Pierre Restany, Michel Ragon, Frank Popper, Alain Jouffroy and a certain number of the leading lights of the critics’ fraternity who had joined us on this adventure, to follow up with a series of events, including La Critique d’art en Europe (‘Art Criticism in Europe’, 1992) and Quelles Mémoires pour l’art contemporain? (roughly, ‘What can be our Memories of Contemporary Art?’, 1996). [5] Taken together, all these events turned the Archives of Art Criticism into a veritable focus for debate.

In the process, we put in place a collection, not only of archival holdings, but of individuals’ writing, intended, in some way, as tokens of our ambition to build the basis for a future archive, at the same time as a living body of literary criticism. Our goal was to establish a direct link with all the members of AICA France, as a means of involving them in the development of the archive. [6] As an added incitement, to encourage authors to entrust us with their texts, we launched the review, Critique d’art, in 1993, as a way both of evaluating their new publications and offering them a bibliographic service that they could not find anywhere else.

J.L. This connection to the French section of AICA offered us more than a welcome opportunity: it was a fundamental element in putting together some archives that could develop in symbiosis with the exercise of individual contributors’ critical practice. Later on, AICA International itself went on to deposit its own archives there.

J-M.P. That was when you had become International President of AICA.

J.L. Yes, from 1990 to 1993, and from 1993 to 1996, as I served two consecutive three-year terms, as President of the Association. That was the moment when AICA had to vacate the premises at Rue Berryer, and move out the archives. So that was how the archives came to be deposited in Châteaugiron, instead.

J-M.P. Had AICA France already turned over some of its archives?

J.L. When I became President of AICA France, in 1980, there weren’t any archives, and there weren’t any premises either. There must have been some documents in the possession of Michel Ragon, Georges Boudaille, Jean-Jacques Lévêque and Dora Vallier, who had been presidents before me, but none of them had passed on any archives to me. What really got things going, as far as AICA was concerned, therefore, was linked to the acquisition of the archives of AICA International, stretching back to 1948. Hélène Lassalle was the first person to make use of them, notably, at the time of the 50th anniversary of UNESCO’s granting AICA the status of a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO). As far as AICA France goes, my own personal archives (very poorly organised, as they were!) were the first to be integrated into the Archives of Art Criticism. I don’t really know whether the holding of Ragon’s work contains any documents relating to his period as President.

J-M.P. No, I don’t think so. At the time, there was not much interest in that kind of thing in cultural circles, any more than there was any interest in academic circles for the traces that had accumulated from years of critical practice.

J. L. The slight interest shown by French institutions in art archives relating to the process of artistic creation is doubtless linked to the history of AICA itself, which, by emphasising its interest in truly contemporary art, was largely shaped in opposition to the traditional beliefs of art historians. This division between the art historians and the art critics may, at a certain time, have strengthened the indifference to the work of collecting archival material. The art critics, for their part, had probably felt such a strong sense of writing for the present that they had paid little attention to the historic dimension that much of their writing wold take on, later. Moreover, from 1981 onwards, and throughout Jack Lang’s period as minister, we exuded a strong sense of wanting to be immersed in the present and of keeping up with the latest, and newest, artistic developments.

Salle de consultation des Archives de la critique d’art à Châteaugiron, 1992, archives internes ACA, collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. D.R.

This didn’t exactly impel people to develop a retrospective, historical perspective. In addition, we have to remember that up until around 1970 universities banned students from writing PhD theses on living artists, or writers. This state of affairs began to change little by little over the course of the following decade, and to have a noticeable impact on the recruitment of new members to AICA France. When I was elected President, AICA France had around 90 members, almost all of them, critics writing for the newspapers or in the art journals. At the time, art criticism in the press was much more abundant and lively, and far more space was accorded to it. Academics weren’t involved with AICA, and AICA didn’t like academics! We have to remember that none of my predecessors had been an academic. However, from 1981 onwards, several members of AICA, such as Gérald Gassiot-Talabot, Michel Tronche and Anne Tronche, in particular, entered the ranks of the Ministry of Culture. In addition, I, for my part, invited academics who were writing about contemporary art, including Hubert Damisch, Georges Raillard, Louis Marin and Georges Duby, for example, to present their candidature, and they were duly elected to AICA. I think that the possibility of starting to think seriously about an archive was facilitated by the relative expansion of the membership, because the membership of AICA had risen to more than 300, including a good number of university teachers, by the time I stepped down.

J-M.P. Nowadays that goes for at least 40 % of new candidates. The disappearance of many publications that had been accustomed to paying freelancers has contributed to this trend, on top of the greater attention paid to contemporary art in university coursework.

J.L. That’s true, as art journalism scarcely brings in enough for people to live on nowadays, and the result is that people wanting to write art criticism usually have to earn a salary doing something else. This situation has profoundly affected the composition of AICA, in the same way as has the tendency to bring art schools closer to the world of academic research, and its criteria.

J-M.P. We have also witnessed the emergence of the curator of contemporary art.

J.L. One of my battles was, indeed, getting International AICA to recognise that the curator of an exhibition necessarily performs a critical function and therefore has a rightful place in the Association. The art world was in the course of inventing new roles, and these had to be reflected in AICA’s composition.

J-M.P. The Archives first gained international recognition at the time of organising the AICA Congress in 1996. All the changes that you have just pointed out then meant that it became necessary to start thinking about the conservation of archives, rather than the simple gathering of documents. This was also the period, when more and more artists were starting to integrate archival material into their work. We attempted to address this, by organising a colloquium on ‘Contemporary Artists and Archives’ (Les artistes contemporains et l’archive). The following years were notable for our participation in the European Vektor programme, in collaboration with the archives of the art market in Cologne, the documenta archives, in Kassel, the Museo d’Arte Moderna, in Bolzano and a couple of other partners. This programme enabled us to adopt international norms for dealing with archives, and to investigate a range of different methods and objectives. Things became more difficult for us after this, in the first decade of the millennium, because we had to take care of a massive collection and welcome and an ever-increasing number of researchers and curators, who were hunting for ‘historical’ documents.

Salle de consultation des Archives de la critique d’art dans leurs locaux actuels à Rennes, archives internes ACA, collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. D.R.

It was then that we laid the groundwork for our academic relations with the National Institute of Art History (INHA), which supported a number of our programmes for dealing with one or another of our archival holdings. At the same time, a substantial grant from the Getty, in 2005, enabled is to catalogue a large part of Restany’s archive, at the moment when we need ed to persuade his widow to hand over to us the remaining part of his archive. The opportunity of organising a large international colloquium on ‘The Last Half-Century of Pierre Restany’ (Le demi-siècle de Pierre Restany) at the INHA , at a time when I was in charge of the Department of Studies and Research there played a decisive role in helping us to develop an evaluative model that we could then follow up with a colloquium devoted to ‘Michel Ragon: The Art Critic’ (Michel Ragon : Critique d’art), in 2010. [10]

J.L. And what is the current situation with the Archives de la critique d’art?

J.-M. P. The Archives have just emerged from a crisis of expansion in an unfavourable economic climate, by creating a ‘Group of Academic Interests’ (Groupement d’intérêt scientifique) (GIS), which was attached to the University of Rennes 2, at the same time that the ownership of the collections was transferred to the INHA. The ‘GIS’ was founded by the following three partners: AICA International, the INHA and the University of Rennes 2, but its Advisory Council also includes numerous university partners, and French and foreign arts professionals, capable of supporting its cultural and academic mission of building up and evaluating the collections. All the necessary conditions have now been created, for us to move on with full assurance to a new stage in our development.

—————-

1. At that time, the ‘Delegation for the Visual Arts’ (Délégation aux arts plastiques) was the department in the Ministry of Culture which was responsible for contemporary art.

2. The Archives had been dismembered, and it took several years to recuperate the different elements of it, with the exception of one part which had been turned over to the Musée national d’art moderne, recorded in a brief inventory that the Archives de la critique d’art has drawn up.

3. Today, the Restany holdings, which were put together from numerous contributions from the critic himself and his family, is the richest and most complex part of the Archive. It covers Restany’s extremely international activity throughout the period from the 1950s to the 1990s.

4. Élisabeth Lebovici, Didier Semin, Ramón Tió Bellido (eds.), La place du goût dans la production philosophique des concepts et leur destin critique (‘The Place of Taste in the Philosophical Production of Concepts and their Critical Destiny’). Actes de colloque, (Proceedings of the Colloquium, Rennes, 1990). Châteaugiron, Les Auteurs & les Archives de la critique d’art, 1992.

5. Quelles Mêmoires pour l’art contemporain? (‘What can be our Memories of Contemporary Art?’). (Proceedings of the Colloquium, Rennes, 1996), Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 1997.

6. The inclusion, by 2015, of nearly 400 holdings of critics’ writings already represented a significant proportion of the overall output in France of the last fifty years.

7. Richard Leeman (ed.), Le demi-siècle de Pierre Restany (‘The Last Half-Century of Pierre Restany’). (Proceedings of the Colloquium, Paris, 2006). Paris, Édition des Cendres, 2009; Richard Leeman, Hélène Jannière (eds.), Michel Ragon: critique d’art et d’architecture (‘Michel Ragon: Art and Architecture Critic’). (Proceedings of the Colloquium, Paris 2010). Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2013.

Trans. Henry Meyric Hughes

![Quelles mémoires pour l’art contemporain ?, Actes du XXX e Congrès de l’AICA, Rennes, 25 août-2 septembre 1996, fonds AICA International [FR ACA AICAI BIB IMP057], collection INHA – Archives de la critique d’art. Lire en ligne.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58d3ea4f1e5b6c804e67e48a/1569587077739-7SKZP0B153OUBA1DH5A0/Ill.+1_Leenhardt+Poinsot.jpg)